Clear scans, cloudy future

Contemplating the possibility of chemo for life and the type of life I wanted to lead (October 22, 2020)

What I posted October 22, 2020:

This week has been a little harried—I had to do a scan on Monday morning, then learned late Tuesday night that they hadn’t done it correctly, forcing me to race back downtown yesterday.

They felt badly about it—apologizing, paying for my parking, and ultimately turning around the radiologist’s report in record time: it hit MyChart just before dinner.

We anxiously reviewed it, trying to decipher the most important sentences: “No suspicious focal hepatic lesion is identified to suggest new residual metastatic disease. All the major hepatic vessels remain patent. The previously described ill-defined hypoattenuation is no longer well visualized.”

Translation: My scan was clean!

We don’t yet know what, if anything, this will mean for treatment. I’m scheduled for chemo again on Monday. While a part of me hopes for a chemo break, a bigger part of me suspects that is not likely what I will hear. And I’m trying to make my peace with that—and stay focused on the good and not the bad.

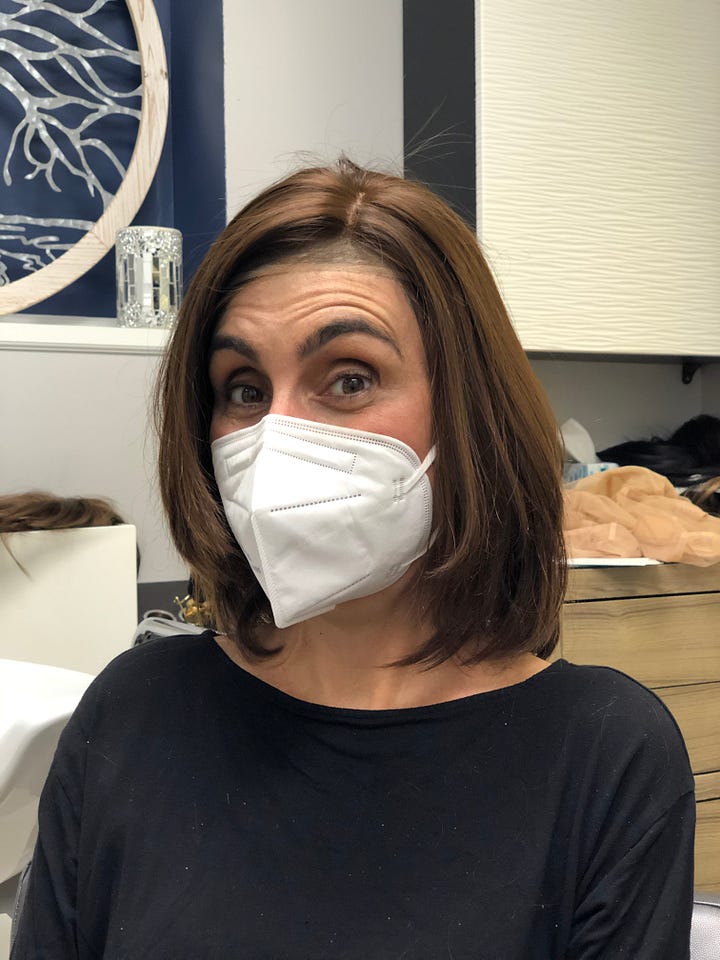

My hair suddenly seems to be leaving by the handful; its demise feels inevitable. Per says I look like a bad ass, but it’s not my preferred look. I’ll start my day tomorrow at a wig store. As soon as I made the appointment, I stopped feeling teary every time I ran my hand through my hair.

I’m so glad to be able to share some good news with all of you, even if my days of looking like a bad ass might soon be over.

Looking back today:

I was a little unsettled ending my last post the way I did.

The optimist in me is always looking for the bright side, the learning, the lesson to be shared.

But the reality of a journey like this is that sometimes it doesn’t come that easily. In fact, it often doesn’t come that easily; and thus as I continued treatment over these months, I posted significantly less frequently.

It just didn’t seem that valuable or interesting to vent about on-going cancer-treatment side effects or the on-going efforts to stay on top of them in what felt like an endless game of Whac-A-Mole.. I’d figure out how to manage one, only to have another pop up. I lost hours a day not only to fatigue, but to the tending of my cuticles, the trips back and forth to the bathroom, the application of steroid cream to my rash. Each evening, I would try to muster the energy to apply first lotion, then Aquaphor, to my hands and feet, pulling on socks and cotton gloves afterward to keep the moisture in place. But as much as this proactive treatment helped, more often than not, I skipped it: my pillow and a last hit of phone dopamine—inaccessible when I wore gloves—typically proved too tempting.

I recall feeling particularly irked about losing my hair, which was happening in arrears of being on FOLFIRI; the Irinotecan is what causes the hair loss, and I hadn’t been on it for several cycles already. My care team and I had reached the same conclusion: it was the combination of 5FU and Vectibix that seemed to be doing the heavy lifting within my protocol, and I saw saving my hair as the silver lining of having to deal with the rash and other accompanying skin issues.

It would still be months before I got the real silver lining: a changed relationship with my daughter that continues to this day.

What I found hardest about all the side effects wasn’t so much their intensity as their duration: they stretched for weeks and months and years, with no end in sight. I’ve heard other female patients describe their experience with chemo as like the first trimester of pregnancy. When talking to men, I told them to imagine trying to live and work with a horrible hangover—forever.

At this point in my journey, I was trying to come to grips with the possibility of being on chemo for life. Maybe scarier still was that I was starting to recognize I ultimately had the power to decide about whether that was what I wanted. Would I ever feel ready to make that call? When, exactly, would I reach the point at which the twins—or the rest of the kids, or even Per—might not as urgently need me?

Right after diagnosis, I had started writing a book to Jack and Delaney in my head: all the things I wanted to be sure I told them, to be sure they knew if I had to leave too early. That book never got written; in part because I didn’t have the energy, and in part because I started to realize that what they really needed to know is how much I loved them. The forced isolation of Covid made it easier for us to spend more time together; and I recall being grateful for every meal we shared.

Like the rest of the world experiencing the losses of Covid—loss of loved ones, loss of control—it was gradually becoming clear that the future held no guarantees. We started to more consciously make the most of the moments we had, conscious that living for the light at the end of the tunnel was no longer a workable strategy, and maybe never really had been at all.

I'm curious to hear how living through Covid impacted those of you who were not also dealing with illness at the time. What insights did you have? What was the most difficult? The best silver lining? Do you find yourself living differently today because of what you experienced?

Thank you for this story and its prompt for me to note my own struggle and renewal during COVID. Not with my own cancer but with the death of my daughter, 42, from cancer in late 2019. I actually welcomed the isolation for my own heart’s healing and my chance to slowly come to terms with the sadness. I wrote letters to her every day, bought myself an e-bike and began a journey to better health than ever. I feel her still as she nudges me toward joy in every moment. She was like that...lived with joy as long as she was here. My cherished mentor❤️

So sorry for your loss.