Here we go! Part two.

Looking back on the one-year anniversary of this Substack (August 29, 2022)

What I posted on August 29, 2022

I’ve been at the office more often recently, and I’ve been bumping into friends and colleagues whose only exposure to me has been via this group / blog.

“How are you??,” they ask excitedly.

Each time this happens, I smile and open my mouth to respond, intending to say that I feel healthy.

But my mouth catches on the “h” …and so instead, I find myself saying, “I feel happy.”

And once it’s out there, I can’t take it back—because a surprised smile has already started to form on the face of the person opposite me, and as it grows, I feel my own widen in response.

I AM happy, I realize again and again—each time jolting me just a little more into the consciousness that, healthy or not, I feel healed, authentic, ready to step into my purpose.

I’ve spent 27 years building marketing muscle; and the last four engaged in the brutal reality of stripping back the person I once tried to be, revealing at last only who I am.

I recall how hard I fought to stay the person I thought I should be: taking my laptop with me (camera off) into the bathroom, alternately napping and setting alarms to get myself through meetings, using any energy I had for work, and not much else. The first time my therapist encouraged me to find value in BEING versus DOING, the concept was so foreign to me that I left the session without really understanding what she was talking about. I answered every question she asked about who I was with what I did; and I almost always started with the words, “I drive value by…”

It wasn’t until I was physically robbed of my ability to drive value by doing anything at all that I started to understand what she meant.

Maybe it’s similar for most first-born children, who start out trying to please their parents; then extend those energies to teachers, coaches, bosses, and friends. Just a few months ago, I saw a quote from Brené Brown that hit me at my core: “When perfectionism is driving, shame is always riding shotgun—and fear is the annoying back seat driver.”

After four years with cancer, I have learned how significant a role fear and shame have played in my own life—and how important it is to finally name them in hopes of letting them go.

Perhaps they had always been there in the background, but cancer magnified their presence and made clear how they worked their tentacles into literally every facet of my life, particularly the parts of me that felt the most irritating, embarrassing, and ugly.

Many cancer patients feel shame, even if they rarely articulate it. I joke that the outward anthem of a cancer patient is the Pet Shop Boys’ “What Have I Done to Deserve This?”—and its shadow anthem is the one a patient sings to themselves in the darkest of night: Everything I’ve Done to Deserve This.

It starts with having gotten cancer at all—certainly at the least convenient time—and moves directly into needing help from friends and strangers; vomiting up your supplements; having no appetite when you know you’re supposed to eat; not drinking your daily green spinach-and-kale smoothie because all you can stomach is a McDonald’s cheeseburger; nodding as the cabbie tells you about his friend of a friend who cured themselves on an alkaline diet; and smiling weakly when someone tells you you’re so brave or such a warrior and you think to yourself, honestly, what fucking choice did you have??

But cancer patients do deserve a choice—to take a path that is not (necessarily) Warrior or Withdraw; to make the decisions they want or need to make without feeling shame; and to recognize and name fear in hopes of being better able to navigate it.

In just two weeks, on September 11, I’ll hit the four-year anniversary of my diagnosis—and I’ll be within striking distance of a five-year survival rate, a goal which should have seemed impossible back when we started this journey.

On that date, I’ll be launching a year-long content series called Strive for Five, where I share an accelerated and authentic look back on my four-year journey.

It will consist of two primary components:

On Substack, I’ll share a regular emailed newsletter which pairs old posts with new commentary, sharing the behind the scenes we didn’t share back then, when we were literally scared out of our minds but taking to social media to pretend everything was OK.

On TikTok, the focus will be less internal and more external, and I’ll share the dark humor of cancer and all its indignities in video form—what I expected versus what it was; the euphemisms of oncologists and surgeons; how to make the java smoothie I could eat when I couldn’t eat anything else; how to use a maxi-pad on your chest when your drains are leaky; ways to play your C card.

If I’m honest, the idea of video content freaked me right the F out; but my wisest advisor insisted it was critical, telling me that it was the intimacy I provided that kept people reading; and that seeing me in sight, sound, and motion was required if I wanted to scale my message.

I procrastinated for weeks, writing scripts that didn’t feel quite right, then tweaking them as people I trusted probed and asked the right questions. Finally, I felt ready to ask my husband Per, who is an art director by trade and creative genius by birth, to start looking for pictures to accompany what I thought I might create.

Then, on Friday, I was in the elevator at Northwestern after seeing my oncologist when he sent the start to a very first video. It looked absolutely nothing like I had in mind—right on brief, but the last thing I would have expected—and it made me laugh so immediately and so hard that everyone else turned to stare.

Suddenly, for the first time I wasn’t worried about video; because I realize that I am married to just the right partner to make this all happen, and that it will be amazing.

If you’re interested in taking this journey back with me, I hope you’ll subscribe on Substack—and encourage anyone you know who might be early in their own journey to check it out as well. (If you’re already signed up on this blog, I’m going to take the liberty to port you over—it’s easy to unsubscribe, and I promise I won’t feel bad if you do.)

You can also find me on Tik Tok as ginabjacobson or Instagram at ginabjac. There’s nothing there yet, but we’ll start posting in two weeks’ time.

I do hope you decide to join me—because everything is starting to fall into place, and I have a feeling it’s going to be amazing!

Looking back today:

I posted “Here we go” exactly one year ago today.

It’s hard to express how incredibly life-changing making this commitment to recap my four-year journey with cancer over the course of my year to five has been.

The idea was selfishly motivated, born of my recognition that I would never manage to write a memoir without the scaffolding of a commitment made to others: in this case, posting twice a week.

After writing the first two chapters, both memory and motivation failed me. I realized I’d have to go through all texts and pictures to piece my journey back together—and thought exposing the process to an audience would keep me on task and might even help someone in the meantime. Even if it helps only one person, my therapist and I agreed, it would be a worthwhile pursuit.

Never in a million years did I anticipate the person it would most help would be me.

Or how much impact might come from committing to a process versus a goal.

Years of professional conditioning have ingrained in me the value of setting goals: SMART goals are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-specific. “Be the #1 driver of organic growth at the agency,” I recall recording as a stretch goal at work a few years back. “Win every pitch on which I play an active role,” was my stretch goal last year.

“Survive for at least five years,” was my goal at diagnosis, when they told me I had 1 to 2 years to live; “Beat cancer completely,” was my stretch goal.

Deciding to do a Substack, on the other hand, was a commitment to process and behavior versus any sort of final objective: write every week, twice a week. I had some vague hopes for what the exercise might yield: material for a future memoir, growth of an audience, a miraculous connection with an editor who would be magically motivated to whisk my musings directly into publication without any of those messy drafting / revising / submitting requirements, etc. But mostly, I just decided to do it.

Years ago, when Per decided to run his first marathon, he asked me what I thought his goal completion time should be.

“You don’t run your first marathon for some goal time,” I told him. “You run your first marathon to run a marathon.”

Substacking has taught me the value of continuing to put one foot in front of the other, consistently if flexibly. My posting regularity was sometimes reduced or delayed in consideration of scans or a bad cold. But their frequency was a commitment I made to both an audience and to myself; and across the past year, it’s only because I made that commitment that I have come to recognize the therapeutic value it held.

It’s hard to overstate how much I have learned across a year of Substacking, or the role it played in my healing:

Persistence versus Perfection: staying on schedule meant forcing myself to oftentimes post without polishing; learning how to let go of 100% perfect allowed me to get exponentially more done.

Impact versus Coverage: choice is at the heart of strategy; and it wasn’t long before I realized I couldn’t deliver consistency across both Substack and TikTok without compromising them both, much less my own sanity. I chose to focus on Substack: harder to build an audience, better for my inner healing. (Although this TikTok is still climbing toward 1M views!)

Growth versus Goal: the more I learned from my journey, the more important growth became to me; and the less primary a goal of survival.

Authenticity versus Approval: reflecting and writing consistently and with the distance of time helped me to see patterns I needed to break: how much I was limiting myself looking for approval where it was unlikely, and hurting myself where it was in conflict with my authenticity; how much more engaged and effective I felt pursuing things that aligned with my beliefs, when my own measure of success was the most important one.

There is a challenge trending on TikTok right now—commit 100 minutes a day to something for 100 days and make $100K. I’m intrigued by the link of value with consistency and find myself thinking about what might happen if I made a commitment like this for 100 minutes a day; or even 50.

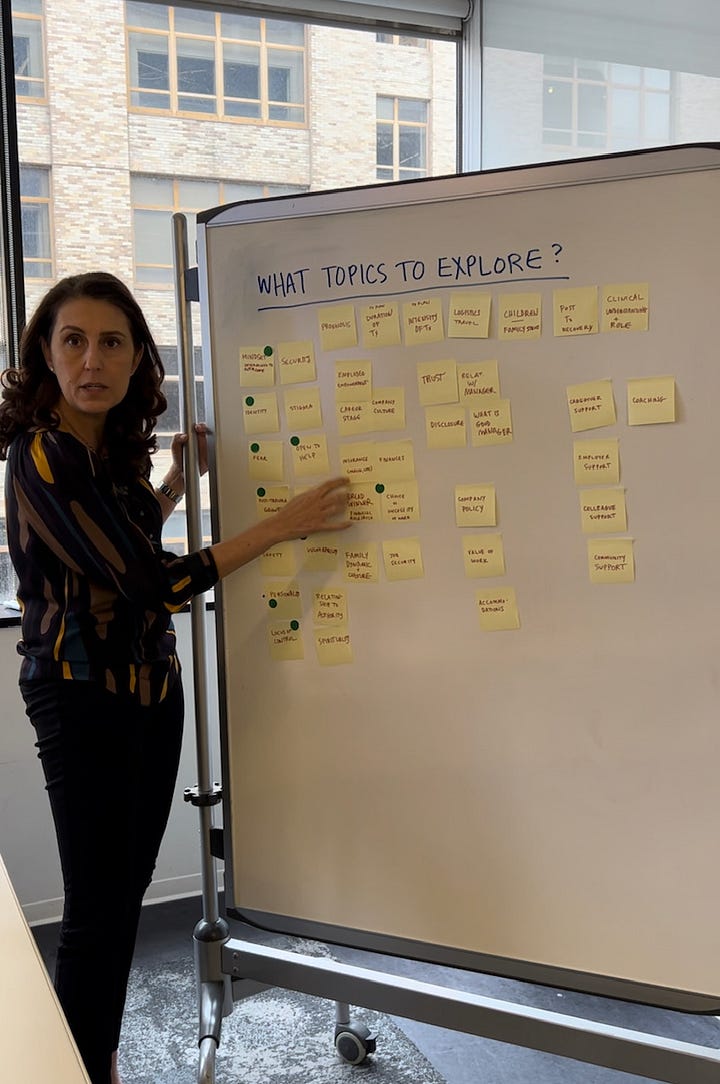

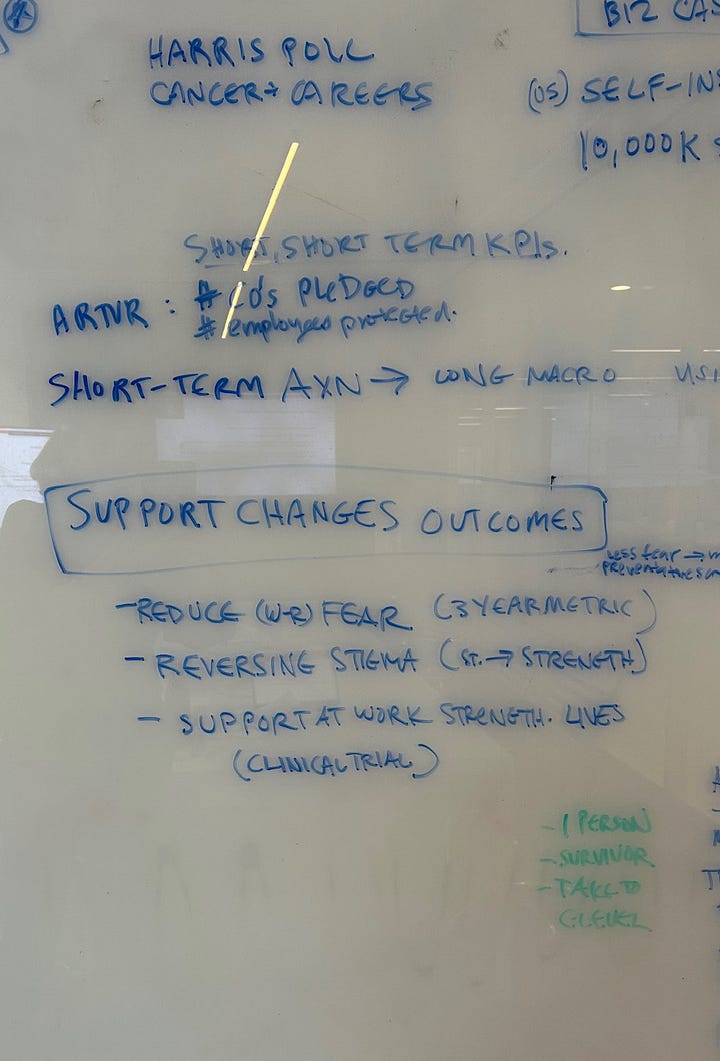

If I were writing a creative brief, my SMIT (single most important thing) would be “Support Changes Outcomes.”

And my RTBs (reasons to believe) would be many: starting with my own story, extending to my professional role leading the Working with Cancer initiative at work, and potentially inclusive of an incredible range of ideas I’ve had, everything from an Etsy t-shirt shop to a research study that creates clinical data proving workplace support positively impacts health outcomes.

I cannot shake the idea that clinical data would change everything. I’ve explored it professionally in several guises since first thinking about it in March, and I’m realizing that the idea falls outside of the purview of an advertising agency, not to mention my own expertise. But when I talk about it, I can feel the swell of potential rise up in my body; and I recognize that I still believe in its power and that I can find a way to make it happen.

I only need to decide.

And accept the possibility that I may not succeed—but that the process of trying will yield impact and learning all the same. That trying would help drive the idea that support changes outcomes—and that alone would be a win.

It mirrors the way I’ve come to think about my cancer journey. Increasingly, I have stopped thinking of winning or losing as solely a function of my survival—but as a function of what I learned from the experience along the way, and what might come from that.

That’s why today, I know I’m winning.

And why I’m excited about making new commitments about what I do day by day, guided by the conviction that support changes outcomes—and opening myself up to the possibility of what might come.

It’s going to be amazing.