Savoring the days before returning to chemo

Enjoyment comes easier when the other shoe has already dropped (April 12, 2020)

What I posted on April 12, 2020:

“I heard back from Dr Kemeny. She agrees that the lesions in the liver are new activity and that you should start treatment.”

“Ok,” I say. I’m not surprised, but somehow disappointed anyway.

I can’t decide if knowing what to expect makes things better or worse. And as much as I do know, there’s plenty I don’t.

It’s a new protocol: FOLFIRI, which replaces the Oxaliplatin in FOLFOX with Irinotecan—affectionately known by oncology nurses as “I ran to the can.” I’m also more likely to lose more of—probably all of—my hair.

In better news, Vectibix, the chemo rash drug, is not being prescribed this time around. I’ve debated long and hard about whether I would rather be bald or rashy (as if the choice is mine), and I pick bald.

Is a good wig considered an essential service?

Chemo during a Covid-19 lockdown is a mixed blessing, with obvious drawbacks: my safety being a critical one. No visitors at my appointments; no visitors period. For now, the kids still go back and forth between houses, but I’m bracing myself for the point where my oncologist asks that we stop.

On the other hand, there’s no travel—for any of us. Life is always a little easier when Per is around, and there’s nobody I would rather have by my side when I’m feeling sick—counting out pills, bringing me toast, administering fluids and disconnecting me from my IV.

We are all together more often, setting the dinner table for six so often the twins have stopped asking how many for dinner.

As crazy as life seems with Covid-19, I’ve spent the last few days purposefully enjoying what’s still normal:

Long walks on the lake in the sun.

Making the food we love and appreciating being hungry for it—and my ability to taste it. Pulling together salads almost every day for lunch (baby greens, apples, blue cheese and homemade sugared pecans—a combo that won’t be easily digestible soon).

Ordering sushi for the last time.

I maybe even snuck in a half glass of very good wine.

It’s been six months since my last round of chemo—and five since my last big surgery. Versus the last time I started chemo, I’m much stronger. I weigh more. And I’m less scared.

But more sad. The kind of sad that takes you by surprise when something little is frustrating or irritating and suddenly you find yourself sobbing for something else entirely: for only getting a few months of normal, for not having taken that honeymoon you said you were going to take, for the toenails that are just now falling out from the first round of chemo, for the hair and the appetite and the butt and the control you are about to lose. For knowing on some level that you weren’t done with cancer but letting yourself be taken away by the idea that you were—for your family as much as for yourself. For just not knowing what you thought you would know.

I feel like this recurrence makes me tragic, which pisses me off—maybe the only thing powerful enough to combat my sad.

“Don’t count me out yet,” says the voice in my head.

I start the next leg of this journey tomorrow.

I’ll have to go by myself—no visitors allowed. I’ll pack my own lunch and maybe stop for a single donut. But I won’t be alone. That much I know.

Thank you, all.

Looking back today:

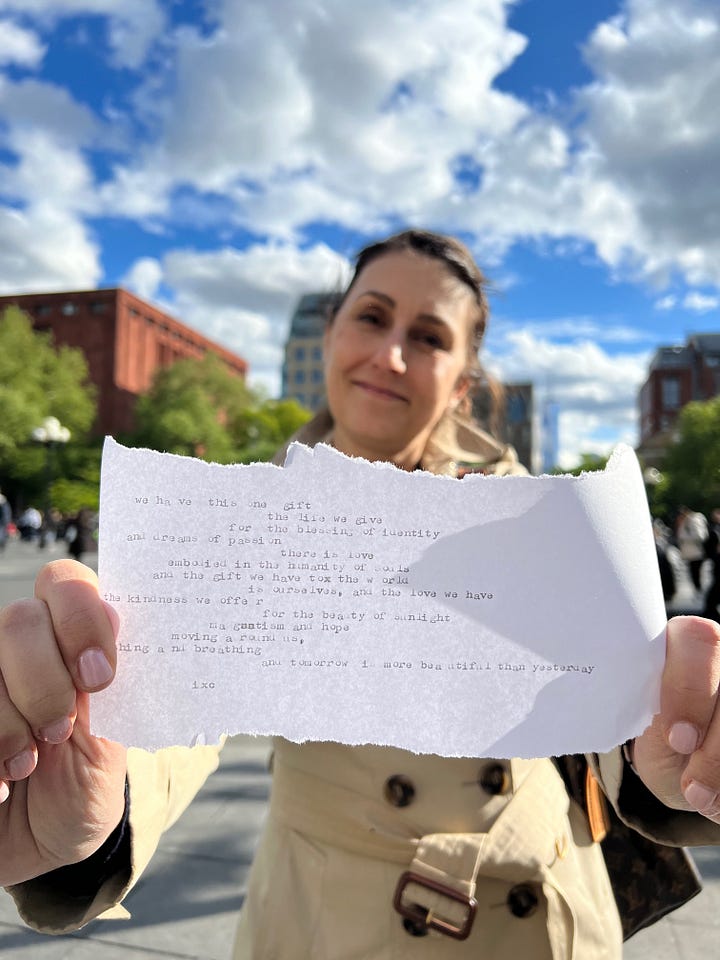

I’ve skipped over this post where Dr Kemeny asked me to delay chemo this post where Dr. Kemeny asked me to delay chemo for a week until she had a chance to review my scans herself. I didn’t hold out much hope that she would reach a different conclusion, but the extra week to enjoy life unencumbered by chemotherapy was still a gift, and I cherished the extra days of appetite and eating.

Here I do a good job of explaining what it is like to resume chemotherapy, having done it previously; the knowledge of what is to come is both blessing and curse.

Less fear, more mourning.

I am struck, reading back on this entry, how conflicted I was feeling hopeful.

For the fact that I am not surprised, but almost apologetically disappointed.

For citing my family as the reason I let myself be “taken away” by the hope that I was done instead of everything my body told me—as if my own desire to be healthy and done wouldn’t have qualified as reason enough.

If I could have articulated it at the time, I might have also told you that I didn’t feel I deserved to be done. I hadn’t finished the mop-up chemo, a component of the protocol which might have brought me greater confidence, even if false. And as such, my penance felt likewise incomplete.

And yet, I recall telling my therapist that my recurrence didn’t make me feel doomed—in spite of the odds, now worse due to my recurrence, I had really never felt that way.

I was, however, deeply, deeply sad to be reentering the brutality of life on chemo that I had hoped to have left behind. And maybe due to that, highly attuned to all of life’s pleasures and enjoying them to their fullest.

A pre-cancer me might have expected that this experience may have been bittersweet, living with the knowledge that they would be soon stolen. In fact, nothing could have been sweeter.

Several months ago, social media pushed me a segment of an interview between Oprah and Brene Brown which helped me to make sense of why:

“If you ask me what’s the most terrifying, difficult emotion we feel as humans,” (Dr. Brown) says, “I would say joy.”

Calling joy “terrifying” may seem strange, but Dr. Brown explains that the fear stems from having our joy taken away. “How many of you have ever sat up and thought, ‘Wow, work’s going good, good relationship with my partner, parents seem to be doing okay. Holy crap. Something bad’s going to happen'?” she asks the audience. “You know what that is? [It’s] when we lose our tolerance for vulnerability. Joy becomes foreboding: 'I’m scared it’s going to be taken away. The other shoe’s going to drop…' What we do in moments of joyfulness is, we try to beat vulnerability to the punch.”

My shoe had already dropped; my vulnerability was full. And thus, I was free to enjoy those joyful moments to their fullest. It occurs to me that both of our trips to Hawaii were taken in the wake of bad cancer news; both were heavenly.

Dr Brown’s quote brings me back to my thought about the ego’s role in scanxiety: perhaps that is just another example of trying to beat vulnerability to the punch?

Almost as soon as I caught this idea on paper last week—and directly after Per posted on Facebook asking people to send me stars—I felt my scanxiety reduce significantly. I felt surrounded by positive vibes; and it became increasingly easy to see the role my ego played in my scanxiety. Each time I played out the possibility of something being picked up on my scan, I could hear the automatic response in my head: “See, you were right.”

Which I could recognize as ridiculous. Beyond scanxiety, every other sign suggested that I was getting healthier and healthier. Intuitively, I felt healthy. But here was scanxiety, the unwelcome marauder, trying to protect me by beating vulnerability to the punch.

“Going back into treatment would suck no matter what—having had a feeling won’t make it any easier,” I told myself sternly, more than once.

And, “Your scan might show something—you’ve been surprised before; but there’s no actual data that would suggest you are recurring.”

The evening of my scans, my blood test results hit my portal—including my CEA, a reliable leading indicator for me. I told Per to look, then braced myself until he confirmed the number was stable. My scan results were there, too, but Per didn’t mention that, knowing that I wouldn’t look. It always feels safer to get the official word at MSK—and this time, we didn’t have to wait long before Dr. Kemeny herself breezed in before her staff to say everything “looked good!”

In the pics Per took directly after the news, I look like a child as Dr Kemeny examines me, feet swinging. When she leaves and we take a pic without my mask on, you can see my shoulders dropped as I smiled at the camera. I wasn’t surprised, but I was certainly relieved.

That evening, we went back to Raoul’s to celebrate over an early dinner with Nathan and Per’s sister Lisa. We had been there for my last scan, and the same waiter we had then joyfully brought out profiteroles in a big caramel cage for the occasion. By 8:30 pm, I was ready to pass out; and I begged off a post-dinner drink to head to bed.

The following day, I had two big Working with Cancer meetings—a Manager Training session facilitated by Cancer and Careers, and a meeting with some of the first companies who signed the pledge. I fell asleep thinking of them, excited about both the meetings—and the rest of my life, as well.

Loved and appreciated the reminder in this one. The way you hung onto delight, your commitment to joy (a theme across all of these it seems)—it made me think of Mary Oliver’s “Don't Hesitate”.

If you suddenly and unexpectedly feel joy, don’t hesitate. Give in to it. There are plenty of lives and whole towns destroyed or about to be. We are not wise, and not very often kind. And much can never be redeemed. Still life has some possibility left. Perhaps this is its way of fighting back, that sometimes something happened better than all the riches or power in the world. It could be anything, but very likely you notice it in the instant when love begins. Anyway, that’s often the case. Anyway, whatever it is, don’t be afraid of its plenty. Joy is not made to be a crumb. –M.O.