The first chemo / the fourth opinion

Starting my treatment - and my healing (October 1 - 3, 2018)

What I posted on October 1, 2018:

I never knew the world had so many stars! Thanks to everyone for all the 💗 and ✨ as I begin my journey back to health. I'm truly overwhelmed.

Looking back today

The first thing that strikes me when I look back on this post is not what I said—because in truth, I didn’t say that much—but how happy I look—almost excited. (Also, how good my hair looks…but that’s a tangent for another post.)

I have come to understand that I am not the first patient who, upon diagnosis, wanted to just DO SOMETHING. Beyond knowing that surgery was essentially a requirement to be cured, the impulse is strong when you first realize something is metastasizing—GROWING—in your body, to just GET IT OUT ALREADY.

It’s only been two weeks since I was officially diagnosed, but those weeks felt like an eternity, and we’ve spent literally every waking moment focused on learning as much as we can, meeting with three different oncologists, having my port for chemo placed, (pausing briefly so that Per can get emergency back surgery…twice), meeting with a Chinese medicine doctor, starting to take his prescribed herbal supplements, getting acupuncture, and drinking daily green smoothies.

So, it’s a relief to finally be at the first treatment, feeling like the road to health and recovery is finally about to start—now we are hitting cancer with the big guns! Here we go!

I already know that I want to find a different doctor, and the nurses are so great that I feel guilty withholding this information, so it’s not twenty minutes into treatment when I confess there is another doctor to whom I am likely to transition my care.

And this is two days before I have my first meeting with Dr. Regina Stein.

The fourth opinion

Mindy, one of Per’s work acquaintances, has messaged us to recommend her as a “doctor who takes a different approach,” and the recommendation feels immediately promising: it takes 16 screen shots to capture everything that Dr. Stein has shared with Mindy to pass along to us, including the questions I should ask and photos of the NCCN treatment guidelines.

She ends the exchange by sharing her motto: “Help patients be their best self-advocate. This starts with education from their oncologist. Science, love, and faith!”

By the time I’m at the end of the text string, I’m pretty sure I’ve found my oncologist.

She’s late to our appointment, and we aren’t too far into our exchange when I start to understand why she will be late to every appointment thereafter as well.

When she finally enters the room, I’m surprised to see a woman of about my own age, with a wide smile and a halo of dark hair. She introduces herself as “Regina,” then looks me in the eyes and puts her hands on my knees, radiating empathy and concern and starts to ask questions.

“Gina, I know these past few weeks must have been a lot. How are you feeling?”

The chemo hasn’t really hit me yet, and so I tell her, “Well, my first chemo was Monday, and I’m not really feeling any side effects yet. So, maybe better than I ought to feel?”

But I have misunderstood her, because what she wants to know is how I am feeling emotionally. This really shouldn’t be that surprising, considering what I’ve come to understand about my life expectancy, but she’s the first oncologist who seems to want to know me as a person versus a patient.

Her questions move beyond me to my family, and she expands her gaze to include Per and ask how he and the kids all doing in the wake of this. She’s particularly focused on the kids: how old are they, what have we shared with them, how are they taking it—she asks so many questions that I find myself wondering if she’s gathering clinical data in some way. But then the conversation shifts to genealogy and her Greek background and the picture of Greece on the exam room wall and whether my heritage is Greek or Italian. It’s rapidly becoming clear why she was late.

Eventually, she begins a physical exam, and spends quite a bit of time feeling the hardness under my rib where tumor is covering my liver, not just confirming it is there, but as if she is trying to get a sense of the disease via her fingers. She apologizes for her cold hands, but her touch is loving and maternal; and in fact, she is a mother, of two children a little younger than the twins.

I find myself telling her that I don’t think I want to see myself as a warrior, that instead I’ve decided to love my way through cancer. When she nods, it doesn’t feel like she is humoring me—it feels like she believes in me.

I confess to her how frustrated I am that none of the other three oncologists were willing to answer my question regarding surgery. She nods immediately—she gets it. “Well, of course you’d be wondering about that. I’d be asking the same thing. The honest truth is nobody knows how you will respond to chemotherapy—and that’s really what will drive whether or not you’ll be eligible for a resection.”

I feel myself relax just a little—not solely because a doctor is finally being honest with me, but because her words give me permission to feel a glimmer of hope.

Dr. Stein knew just as well as the three prior oncologists that my chances of ever becoming resectable were very, very slim.

The difference was that she prioritized my hope over her own ego.

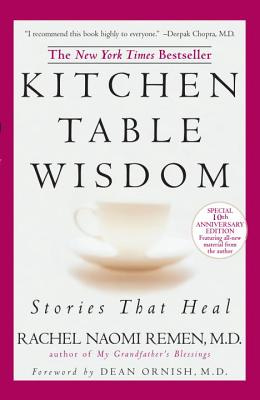

Years later, I would read a poorly titled but extremely insightful book called Kitchen Table Wisdom. It suggested that the ego is so powerful that—subconsciously—an oncologist would feel better being right about a prognosis than that a patient unexpectedly survive. Ego serves a key need: it drives our decisions about who we are and what we do, developing our identity. But, in fields like medicine, where regularly being right is highly valuable, the ego is essentially trained to play a dominant role.

This framing immediately changed the lens through which I considered what any of my doctors might say about my chances—and helped me to feel more comfortable tuning into my own intuition.

A master class in fear / ego

I’ve come to think of my four-year cancer journey as a master class in fear; and most of the coursework was focused on understanding ego—my own, in particular—and what might happen if I better understand its relationship with fear, and thus, its role in driving the way I have chosen to live my life.

Dr. Stein was the first oncologist who subverted her ego enough to believe in me—in spite of the scans that showed 80% of my liver covered in tumor, in spite of all of her medical experience that suggested what was most likely to happen—she offered no promises, but her belief gave me hope, and the permission to believe what my intuition told me: that I wasn’t doomed, that whatever happened would be a good thing, that I would learn something from the experience.

At the time, I thought of “not doomed” as “not going to succumb to this.”

It would still be years before I would understand the difference between healthy and healed.

Not to mention how much she cared about getting you better and at least giving you a chance. She definitely gives you a heart full of hope. Or I live what she says, We stuck a crowbar in the door so it stays open for options. She’s a medical miracle worker. You keep up all the hope she gave you. She believed in you! I know her practiced changed, but let’s both keep her in victory lane.❤️

I’ve always said that Regina is a holy person walking the Earth. She’s saved my life from blood clots on my lungs when I was in the ICU. Then became my oncologist when I got kidney cancer. I knew she was the one for what you needed. Thank goodness you felt her energy the way I thought you would. She’s a treasure. And a beautiful friend to this day.